Have We No Decency?

Virtue is not just a matter of signaling

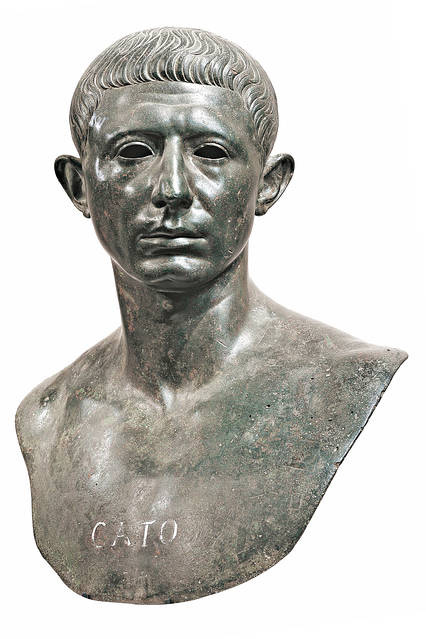

Our Founders believed that republics ultimately rest on the virtue of citizens. While a monarch could govern through fear or awe, a republic depended on the willingness of citizens to subordinate their personal interests to the greater good--to abide by the rule of law, to accept the majority will even when it differed from their own. From their reading of Cicero and Cato and Roman historians like Tacitus–an obsessive preoccupation among educated people on the late eighteenth century–they had concluded that the Roman republic had been sustained by the selfless patriotism of its leading figures, and had collapsed into tyranny when ambitious, self-seeking men like Caesar came to the fore. The Founders modeled themselves on classical heroes: John Adams signed his letters to Abigail “Brutus,” and Abigail signed hers “Portia” (Brutus’ wife).

Our Founders weren’t naive. Because they knew that most men were not in fact “disinterested”--the virtue they admired above all–they designed the Constitution as a machine to check tyranny and encourage the reasonable behavior of citizens. But they still feared that, like Rome–and like King George’s England, whose “corruption” they much exaggerated–America would collapse into tyranny if the people became vicious. That is why they put so much stock in education. As Horace Mann, the patriarch of the “common school” movement, put it, “It is not more certain that a wise and enlightened constituency will refuse to invest a reckless and profligate man with office. . .than it is that a foolish or immoral constituency will discard or eject a wise man.”

Our Dangerous Experiment

It is not more certain. . .that’s a troubling reflection. We have just elected a man who sometimes openly avows, and at other times coyly declines to disavow, his intention to rule outside the law. Some people voted for him precisely because he promised a form of one-man rule they believed in, others voted for him to bring down the price of eggs and shrugged at the prospect of tyranny. The Founders would surely say that if the American people have become so debauched as to choose such a man the second time, with their eyes now fully open, they have, like the ancient Romans, lost the will to sustain a republic. That is what Benjamin Franklin meant when he said–if he did–”a republic, Ma’am, if you can keep it.” Perhaps we can no longer keep it.

Would they be right? After all, we don’t think about democracy the way Franklin did. The great historian Gordon Wood observed in The Idea of America that the Founders envisioned a patrician republic in which an elite with the financial and social independence to be truly disinterested presided over what they regarded as a squalid clash of interests. That language began to fade as old Federalists like Adams gave way to new men like Andrew Jackson and Martin van Buren–as the republic became truly democratic. Today we believe that a system of parties channeling colliding interests, and the regular rotation of power enabled by free elections, allows democracy to flourish without requiring a citizenry devoted to Roman self-sacrifice. Virtue is irrelevant.

Maybe, on the other hand, we are performing a very dangerous experiment to see just how cruel, ignorant and self-seeking we can become and still hold on to our democracy–or rather our liberal democracy, for the question we face is not whether we will have a government that reflects the majority will but whether Donald Trump will wield that majority bludgeon to smash the rules, crush the opposition, terrorize the marginal. Democracy only requires that we accept electoral outcomes (which we’re not very good at either). It is liberalism, with the rule of law and the full panoply of individual rights, that calls upon our civic virtue, above all our willingness to accept the full humanity and equality of those who are not like us or do not agree with us.

The language of virtue discomfits liberals. We regard talk of morality as hostile to the expressive individualism that is our deepest ethos. Whose virtue, we think? Yours? Conservatives, of course, speak morality as their native tongue. As Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously put it, “The central conservative truth is that it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society.” Moynihan went on to say that liberals understand that “politics can change a culture and save it from itself.” That’s a deeply important corrective, but, Moynihan thought, an inadequate response to public life. The only lever liberals know how to pull is the one marked “government policy.” But changes in tax rates and infrastructure investment will not save the culture from itself. If we have lost our sense of decency, policy, by itself, will not restore it.

How Do You Leach The Poison From A Culture?

Every single thing that Donald Trump will do over the next four years will make the work of restoring decency to our lives harder. I worry that the damage he will do to government agencies and political practices will be easier to overcome than the damage he will do to our values and our civic culture. The fuel on which he runs is enmity. Trump seems to vindicate the diabolical view of the Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt that politics constitutes not a clash of interests, or of values, but of “friends” and “enemies.” A good political leader is one who successfully organizes hatred. Trump seems equally determined to prove Schmitt right in regarding liberal democracy as a contradiction in terms..

Where, then, should we put down our shovel? Of course we need to fight every effort to smash, crush and terrorize. But we also need to ask how we can sustain what remains of our civic culture until Trump passes from the scene. The answer, I think, lies all around us. We need to promote new venues of public discussion and debate. If we cannot make social media less toxic, we need to establish new platforms that seek to bring together the not-like-minded. We need to prop up local newspapers as well as national reporting.

The Founders would not have hesitated to supply an answer of their own: the schools must serve as the bulwark of democracy. “In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion,” George Washington said in the Farewell Address, “it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.” We have, it’s true, practically discredited the faith of Washington and Jefferson and Horace Mann that universal public schooling would produce mass enlightenment. Mere exposure to twelve years of schooling has not given us a respect for knowledge, acquainted us with our history or made us proof against tyrants. But we can and must do better; that is the thesis of the book I am now writing on civic education.

There is work to be done. Not all of it lies in Washington.

So, so terribly true.

I think that the most telling (about us!) of Trump's challenges to our liberal democracy are the ones least discussed: the powerful ideas he embodies, and the paradoxical appeal of the amoral norms he flaunts. I discuss these in my two-part post, "Trump, Politics and Climate" in my Substack "Light Not Heat".

https://open.substack.com/pub/lightnotheat/p/trump-power-and-climate-part-1?r=4oms8&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true